Natalia Martinez Paz was hiking the John Muir Trail, which winds along California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, in August when a chance encounter stopped her in her tracks.

“I remember this was a total shock to me,” she says. “I’ve never in my life seen this. It made me so happy, and it’s kind of sad how happy it made me.”

It wasn’t the idyllic Yosemite peaks or the giant trees in Sequoia National Park that prompted her reaction, but rather a group of 16 hikers.

“Every single one of them was Latin,” she says. “They looked like my parents. They sounded like my parents, with very thick accents or broken English. I remember being totally shocked. I’m 36 and I’ve been backpacking since I was eight. I’ve never seen people who look like my family (on the trail).”

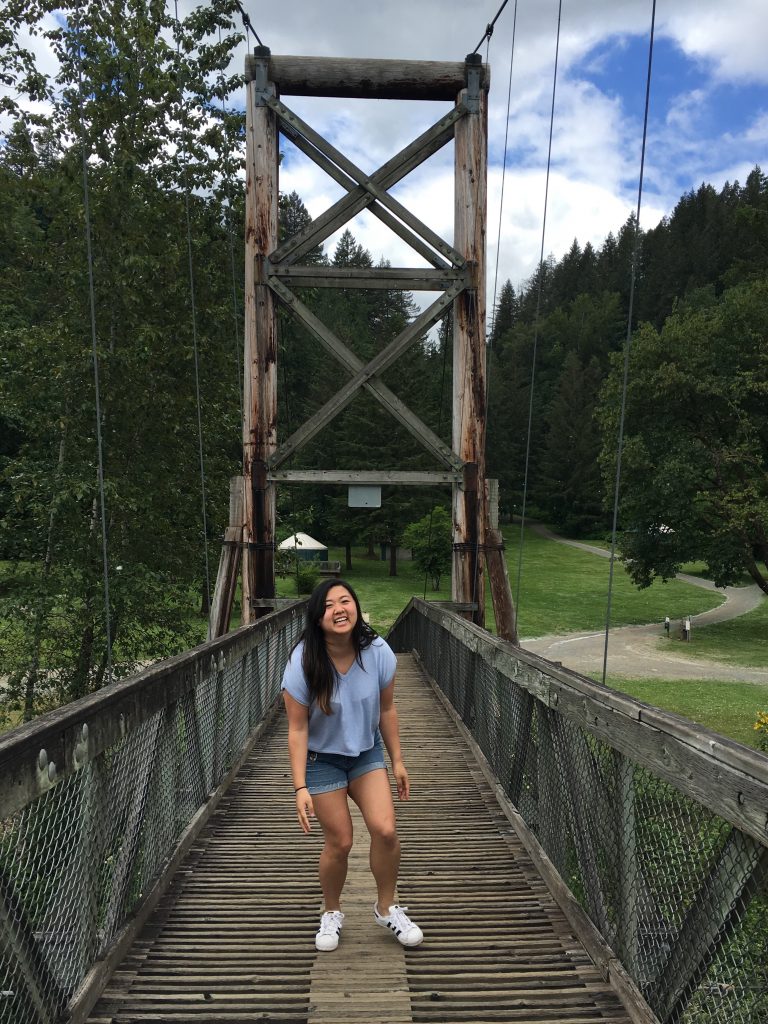

Martinez Paz, whose parents immigrated to the U.S. from Colombia, shares this story with about 20 other people gathered in a circle in the middle of Tolt MacDonald Park in Washington, just over 40 kilometres east of Seattle.

It’s an unseasonably warm fall day in late September and the group—made up of people from various backgrounds, hailing largely from the Pacific Northwest—has travelled to this sprawling park nestled next to the Snowqualmie River to discuss exactly this issue: diversity in the outdoors.

They’ve come here to take part in the Refuge Outdoor Festival, a three-day camping experience that’s geared towards people of colour, with the goal of “building community through outdoor recreation, conversation … music and art that appeal to a diverse and inclusive audience,” according to organizers.

This particular session, one of many running throughout the weekend, is called “A History of Communities of Colour in the Outdoors,” and is led by Christopher Chalaka, the founder and executive director of Outdoor Asian.

“This workshop has been part of a greater project of resurfacing histories that haven’t been taught in schools, that we don’t come in contact with in general mainstream media, and sort of bringing and surfacing histories from our own ancestors’ lives, telling stories from our own experiences, as well as adding to our culture of the outdoors and what that looks like to today,” Chalaka tells participants. “And not just necessarily wanting to just join the current outdoor culture, but instead creating our own outdoor, mainstream culture in all its diversity.”

The participants share stories like Martinez Paz’s for over an hour about how their families have historically connected to the outdoors—from gardening to walking to more traditional outdoor pursuits—and what it’s like to be a person of colour in a predominantly white space.

But the festival is just one part of a greater movement currently underway. Spurred primarily by people of colour, and supported by allies and, slowly, even some within the outdoor industry, efforts to make outdoor places and sports more accessible to everyone are producing tangible change.

From hiking to climbing, skiing and snowboarding to mountain biking, in the U.S. and closer to home in B.C., they’re creating conversations, collecting hard data, breaking down barriers, and bringing people together in an effort to make the outdoors—the most basic of shared public spaces—a place everyone feels comfortable accessing, regardless of their colour, sexual orientation or gender.

Chevon Powell

Founder of the Refuge Outdoor Festival

In 2015, Chevon Powell was heading out on her first solo backpacking trip.

While driving at night to the Vermont hotel where she was staying before hitting the trail in the morning, a cop pulled her over.

“He asked me what I was doing in the area,” Powell recalls. “I said, ‘Outdoor recreation. I’m going backpacking.’ He told me my story was unbelievable and called for back-up … even though you could see my hiking shoes in the backseat. My backpack was in the trunk … In that moment, it was terrifying. It was night, I was by myself and it was only me and the cops. It was in 2015 when Michael Brown had already happened; Sandra Bland had already happened. All those situations, they make an impact on people that look like me because I don’t know what’s going to happen. “

The underlying message was clear to her: “The narrative in America is people who look like me—a plus-sized, black woman—are not outside. That cop couldn’t see that part of me being acceptable and OK.”

The truth is Powell has a long history of outdoor accomplishments—and it wasn’t the first time she’d heard of black women being underestimated in that way.

She recounted hearing about a mountaineer organization refusing to let the first black woman who climbed Mount Everest join them until she took a basic climbing class.

Aside from outright discrimination, Powell acknowledges people of colour have faced other barriers to accessing the outdoors. “There’s been historical trauma, there’s been historical implications on why people of colour in certain times in America’s past did not participate in the outdoors—because it wasn’t safe,” Powell says. “So some of our numbers are low. In the South, there’s still a, ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen to me out in the woods (mentality)’ because, frankly, stuff happened out in the woods. We have to look at what have been those issues in getting people outside because if you don’t pay attention to that, you’ll say, ‘Well, people of colour don’t do it because they just don’t.’ No. A lot of times this is passed down in our families.”

After sitting with that traumatic experience and grappling with these issues (along with living through a startling amount of personal tragedy, losing 12 family members in just one year), Powell decided to take a leap and put her skills as a long-time event planner to work, organizing the Refuge Outdoor Festival. With her company, Golden Brick Events, she had worked on plenty of corporate events, but the festival was her first foray into a “public-facing” event.

“This is what I can do to make change in the world,” she says. “Life happens. A lot of hard stuff is going to happen, so we all need to be using our gifts, our talents, our knowledge to make the world a better place. Refuge did that for people, for a moment. Maybe it’ll have a greater impact.”

This year’s festival attracted about 140 participants throughout the weekend, where they talked about issues of race and the outdoors, attended sessions teaching practical outdoor skills, and danced the night away.

“My focus was representation and conversation and (asking) how do people engage afterwards?” Powell explains. “It made me really happy people got what I was trying to put together and actually were able to take the time for themselves and enjoy the event. People are actually starting to take action and post events. I went to an event (writer Alice Walker speaking in Seattle) and ran into five people from the festival. A few were hanging out together.”

Plans are already underway for a second installation next year.

“My request for (attendees) as they left was, ‘Yes, you have this excitement of this moment. Don’t let it die in this week,'” she says. “Go have more of this (type of)conversation.”

Charlie Lieu

#SafeOutside

Charlie Lieu can be described many ways: as a data scientist, a climber with 25 years experience, a strong, all-around-outdoorswoman who revels in the opportunity to compete with men.

But, as of nine months ago, she’s also become a leader in the growing movement of people addressing the issue of sexual assault and harassment—in this case, in the climbing community.

“It was really interesting because I have experienced a lot of sexual harassment climbing, especially when I was younger. But I was somehow, like a lot of other people, able to compartmentalize that,” Lieu says. “I’d always think, ‘Oh, climbing is so wonderful and inclusive.”

That all changed when one particular man—a famous and well-loved member of the climbing community—attempted to grope her. “He didn’t succeed, so I tried to blow the whole thing off,” Lieu remembers. “I saw him grope two other women, but nobody made a big deal of it … What surprised me was how scared these women were to come out and speak about their experience. When I pressed it, one woman said to me, ‘There was a woman who came out to speak against this guy and she was essentially ejected from the community.'”

Lieu says there were six women in total with stories similar to hers who did not want to speak out. So, instead of pressing them, Lieu decided to approach organizers of an event that was set to honour the man and share her story on her own. A major donor dropped out and “that’s when shit hit the fan,” she says. “It took about five weeks of fighting with some of the executive directors—a few didn’t really believe me or understand what I was trying to say. They said things like, ‘We’re not going to ruin a man’s reputation over innuendo.’ I said, ‘Excuse me. It was not innuendo.’ I had this huge wake-up call that we’re not any better as a community compared to the rest of society.”

Armed with skills as a data scientist and a management consultant, she decided to do something about it—and #SafeOutside was born.

“The first thing I thought was, ‘I need to collect data and see how big of a problem this is,” Lieu says.

With an idea in the works, she reached out to her friend Katie Ives, editor-in-chief of Alpinist Magazine. From there, the two reached out to other magazines and organizations from across the U.S. and Canada—including the Alpine Club of Canada—and even further abroad to distribute a survey asking climbers about sexual assault.

In total, 5,339 people responded. “It is a huge sample size,” Lieu says. “It’s one of the biggest surveys ever done in the world on sexual harassment and assault.”

The major finding: one in two women have experienced sexual harassment or assault while climbing—that’s higher than the average of one in three women who will experience sexual violence in their lifetime, according to World Health Organization statistics from 2016.

More specifically, 47.3 per cent of women surveyed and 15.6 per cent of men said they had experienced some form of sexual assault or harassment while climbing, ranging from unwanted groping and kissing to verbal harassment and rape. Fifty-four of the respondents—42 women, 11 men and one person who didn’t specify their gender—revealed that they had been raped.

“People either stop climbing or stop climbing with people they don’t know or men altogether or (climb) in different ways,” Lieu says. “I think the goal for me, personally, and for my two partners (including Dr. Callie Marie Rennison, a renowned victimologist), is to create not just awareness in the outdoor industry, but also to give people tools to address it.”

To that end, the team has developed a toolkit complete with best policy and procedures for outdoor organizations to follow, educational materials with information on things like how to properly respond to victim disclosure, and bystander intervention, as well as basic information on what, exactly, constitutes sexual harassment.

Lieu says she first decided to take action, in part, because of similar training she received as a volunteer director for the Washington Trails Association.

“I wasn’t woke enough to do this a year ago, but I am now,” she says. “I talk to women who are exactly where I was a year ago who say, ‘What’s the big deal? That’s just the way the world is.’ A big part of my drive is to educate them—and educate men, too.”

Christopher Chalaka

Founder of Outdoor Asian

After graduating from college and moving from the Pacific Northwest to Albuquerque, N.M. for a year, Christopher Chalaka noticed one big difference on the trails in the Southwestern state.

“I noticed people of colour everywhere,” he says. “Like brown people, a lot of people speaking Spanish, and I was just floored. It made me think, ‘Wow, it could be different.'”

Chalaka’s father is originally from South India, while his mother immigrated from a fishing village in Taiwan, but he grew up in Everett, Wash., located between Bellingham and Seattle.

“If you get off the beaten path anywhere outside the main trails, it’s still super white,” he says of Washington hiking. “I found out about Latino Outdoors and Outdoor Afro and I was like, ‘Alright, I’m joining Outdoor Asian. Where is it?'”

It turns out the group didn’t yet exist.

Inspired by the two groups’ social-media accounts, which showcase people of colour exploring the outdoors, he decided to take matters into his own hands by launching a Facebook page, then an Instagram account.

Shortly after, José González, founder and director of Latino Outdoors—which, in addition to its social-media accounts, is a non-profit organization that connects Latino communities with the outdoors—invited Chalaka to join the organization’s leadership conference in Oakland, Calif. “I was totally fanboying over that,” he says. “I saw they created this amazing community … (with) people out of the state and in different regions. I was like, ‘This is amazing. Everyone is barbecuing, speaking Spanish, expressing the culture in the ways they want,’ and it was really beautiful.”

In the two years since launching, Outdoor Asian has hosted several meet-ups and attracted over 1,700 followers to its Instagram account, which features stories of Asian people as they explore the outdoors.

There’s also been an influx of similar social-media accounts in recent years. Alongside those that originally inspired Chalaka, they include Brown People Camping, Unlikely Hikers and Indigenous Women Hike, to name just a few. While social media can be overrun with users curating shallow and incomplete versions of their lives, these accounts seem to be the antidote, aiming to lift up and encourage their followers.

“For the new generations, it’s important for them to have role models and mentors,” Chalaka says. “(People) feel pride about their community. They want to feel like their community is represented and feel like their voice is being heard, because there are big decisions being made in retail, environment, (at) non-profits and they affect people of colour, but sometimes we might feel invisible.”

For its part, Outdoor Asian has seen submissions for features and messages from around the U.S. and in Canada, too. “People aren’t that far, but we have this border,” he adds. “We share a lot in common.”

Going forward, Chalaka hopes to grow the community. “My vision would be to create a platform where we are adding to the outdoor narrative in a specific API (Asian-Pacific Islander) lens and a creation of a space where we can speak about issues that are pertinent to our community and the communities that are adjacent to us and creating community,” he said.

Promoting diversity in mountain biking

Jay Darbyshire’s moment of clarity arrived after the controversy.

Back in 2016, a trail runner in Kelowna, where Darbyshire lives, came across trails with offensive names like “Squaw Hollow” and “TheRapist” and wrote about it in a blog post, which local media picked up. As the field-program coordinator with the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) and co-chair of the IMBA Canada BC council, Darbyshire knew he had to respond.

“I started to evaluate what we do as a community and how that affects our ability to be effective as mountain-bike advocates,” he says. “We can’t do the work we do without addressing these things.”

In part, the epiphany resulted in IMBA partnering with the North Shore Mountain Bike Association to host the Western Mountain Bike Advocacy Symposium. The theme of the October forum was “Building Diversity in the Mountain Bike Community.”

The day-long event attracted mountain-bike organizations and enthusiasts from as far away as Canada’s East Coast, the prairie provinces and Vermont, Darbyshire says.

“Personally, I went in without expectations,” he adds. “I came out of it feeling empowered, informed and like we sparked a little bit of change that’s going to outflow into various areas where the participants came from.”

As a white male in his 30s, Darbyshire admits he slots perfectly into the predominant demographic of mountain bikers. But his personal motivation was to give others access to the sport.

“Mountain biking saved my life, in a way,” he says. “The idea that our behaviour can disenfranchise or alienate someone through our actions, it pains me to think mountain biking might not save someone else’s life because it might not be something they can pursue.”

What emerged from the symposium was a list of concrete ways for the various attending organizations to help make First Nations, women, youth, LGBTQ2i+ and differently abled people feel welcome in the mountain-bike community. It includes things like using gender-inclusive logos, imagery and pronouns, standing up to “toxic behaviour,” hosting pride events, and adopting policies that support Indigenous reconciliation.

“The inherent masculinity of the sport, or inherent culture that portrays itself as being an extreme, aggressive, male-dominated sport, that’s one of the barriers,” Darbyshire says. “It’s hard for someone to want to participate in an activity if they don’t see themselves reflected (in it).”

While Trevor Ferraro, manager of operations for the Whistler Off Road Cycling Association (WORCA), says he’s never felt a divide as a mountain biker of colour, he agrees that more needs to be done to help attract a more diverse set to the sport.

“I don’t notice it so much on the trails,” he says. “I interact with a lot of the members through the events we have and I oversee camps we have. I find that people come from all over to live in Whistler … More people have quite diverse backgrounds already, but that can be expanded in terms of the people involved.”

Ferraro attended the symposium representing WORCA and says the organization has already implemented some of the suggestions. For one, WORCA plans to host more social events with less of a competitive focus next season—aimed at beginners—as well as improving youth access to the sport and organizing additional women’s events.

“We have 30-per-cent female and 70-per-cent male (membership), but we’re looking to increase that,” Ferraro says. “We know there are more female riders, so we want to represent that.”

That said, many organizations and companies at the symposium had set a goal of 25-per-cent female representation, he added. “(Mountain biking) is definitely growing. Hugely,” he says. “Snowboarding has plateaued for a long time. (But) you look at the numbers in the bike park and on the trails, it’s growing by a significant amount.”

To that end, Darybyshire believes it’s also time for the sport to “grow up.

“I was never in a place where I saw it as a sport as not open to me, so I don’t have that frame of mind to see where people are coming from, but I want to work towards being a community that is open to everyone,” he says.

First Nations representation in skiing and snowboarding

When Court Larabee read the job description for Whistler Blackcomb’s (WB) new Indigenous Relations Specialist position, he felt like the role was tailor-made for him.

“It felt like something I wrote myself,” he says.

It turns out, WB felt the same way; Larabee has held the position for the last six months.

“My role is a key commitment within our 60-year relationship with the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations,” Larabee says, referring to the landmark agreement the ski resort signed with the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations in March last year. “The role is mandated to focus on building employment opportunities for both nations. A key component of my role is executing Indigenous HR strategy with both nations.”

On top of helping WB, owned by Vail Resorts, become an “employer of choice” for Indigenous workers, Larabee is also tasked with building cultural inclusiveness at the company.

“What we’re going to do to move the needle over the next couple years is see if we can get the kids involved in recreation—we can get them through the school program into a season-pass program—at the same time they get to explore Whistler Blackcomb … and have an affinity for wanting to work with us,” says Sara McCullough, WB’s director of government and community relations.

On top of that though, it’s important for Lil’wat and Squamish Nation youth to have access to their traditional territory, she adds.

“It’s one of the things elders in the community have been interested (in),” she explains. “I see that growing.”

Employing more local Indigenous people has long been seen as a mutually beneficial solution to Whistler’s labour shortage. WB wouldn’t reveal how many Indigenous people it currently employs, but in October 2016—shortly after Vail Resorts took over WB—Joel Chevalier, then-vice president of employee experience, told The Question (Pique’s now-shuttered sister paper) that of WB’s some 4,100 employees, only 11 were Indigenous.

On top of being tasked with helping improve those numbers, Larabee—who is originally from Thunder Bay, Ont. and is grandson of the Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation’s Chief Thunderbird, as well as the descendant of five chiefs from the past 120 years—also pulls double duty as vice president of the First Nations Snowboard Association, which runs the First Nations Snowboard Team (FNST).

Started in the Sea to Sky corridor in 2004, the organization now has six divisions across Canada and boasts about 230 members. Its goal is to get Indigenous youth on a snowboard—with many going on to a competitive level—all while teaching them about fitness, nutrition and healthy living.

“Our season is looking bigger and brighter than it ever has,” Larabee says. “Our numbers are up in the area, our coaching staff is up and the community support is greater than ever.”

Part of the FNST’s success is that it addresses some of the barriers local Indigenous youth face getting on the mountain—namely transportation and purchasing pricey gear. “We find any gaps in gear and take donations from the community and do callouts to fill any voids before the season starts,” Larabee notes.

The magic, though, is how skiing and snowboarding can be a great equalizer.

“When the kids show up to the hill, when they put their goggles on and their jackets on, there is no unconscious bias anymore. This is the way to even the playing field,” Larabee says. “When they have just a little smile showing through, that means everything to me. They feel like they’re welcome, that this is their home. This is their territory; they should always feel welcome here.”

Going forward

In October, Mountain Equipment Co-op (MEC) issued an apology. In an open letter, CEO David Labistour started by asking, “Do white people dominate the outdoors?”

According to the outdoor company’s own survey, they don’t at all. But, Labistour pointed out in the letter, MEC’s advertising doesn’t reflect that diversity.

“This initiative isn’t about patting ourselves on the back,” he wrote. “It’s also not about me, another straight white male with a voice in the outdoor industry. This is a conscious decision to change, and to challenge our industry partners to do the same.”

In its most recent annual membership survey, MEC found that people of colour were actually more likely to be active in the outdoors than white people.

“It’s not just advertising, it’s the images on your website and store displays. It’s how you present yourself as a brand,” Labistour said in an interview with Pique shortly after releasing the letter. “If we want to be an inclusive, Canadian-based organization that represents the demographics of Canada, and particularly the communities we’re in, but everything visual you see is white, and most of our staff is white, we’re not going to be seen as a relevant brand to those people.”

(In November, MEC announced Labistour would be stepping down in June, but did not disclose the reason.)

As many people have pointed out, outdoor-industry advertising has long perpetuated the image of the outdoors as the domain of slim, white, young people. But as people of colour continue to push the conversation around diversity in the outdoors, slowly, some companies are starting to listen. (It also doesn’t hurt that appealing to more diverse demographics could positively impact their bottom line.)

“I think there’s a shift happening because of social media,” Powell, founder of the Refuge Outdoor Festival, says. “We weren’t part of the industry. There weren’t as many people who looked like us. Once your eyes are opened, you see (that’s not true). Social media is playing a huge role in that. We’re all finding our communities … We are here and present in this community.”